The Cuddles Foundation helps kids with cancer get the best possible nutrition

Purnota Dutta was living the good corporate life. An MBA from the Indian School of Business, she headed marketing for one of the largest online brands in the country, and like many good corporate citizens, pledged a part of her salary to a cause; in her case, the Tata Memorial Hospital.

She was on maternity leave after the birth of her first child, when she decided to see for herself what the hospital was doing with her money. “The moment of epiphany came when I was crossing the last ward and there was this little girl — just a few months old — whose face I couldn’t see but whose legs reminded me of my daughter’s legs. It was an extremely emotional experience, because we are not used to seeing children undergoing chemotherapy.”

Ms. Dutta went straight to hospital’s social worker, and said she wanted to do more; what were the options? The answer she received “sounded strange” she says, but was to decide the course of her life. “She said, ‘We get money for treatment all the time. But we do not get money for food.’ It didn’t make sense, because as Indians, the first thing we think about is khana. We give away food, and here there were little kids who weren’t getting enough to eat.”

She immediately diverted her funds to food, and every time there was a requirement, the social worker would message her. Soon, the requirement far exceeded her personal funding. Then she started tapping her friends, convincing them to give up their birthdays and anniversaries. The corner office was no longer alluring. She had found her calling. She started the Cuddles Foundation in 2011, beginning with sourcing nutritional supplements — Pediasure and Peptamen Juniors — for children with cancer, from various distributors in Mumbai. As the Foundation kept growing, it started addressing every issue around nutrition, with doctors telling them what they required.

Focus on paediatrics

Ms. Dutta was clear that the Foundation’s focus would be paediatrics, simply because “it was a cause that resonated with me.” For the first two years, she took it slow. “Like any other startup, there was a go-to-market plan in place. Till 2013, we were testing our solution, trying to make sure it gives us the maximum return on investment.”

Next: building capacity at hospitals by providing nutritionists; the Foundation now has 24 of them on their rolls. From six hospitals, it now covers 17, in nine cities, with more than 18,000 child interactions in 2015-16. In five hospitals in Mumbai, Cuddles covers about 700 children every month.

The nutritionist is at the heart of Cuddles’ programmes. If a child walks in for treatment, she assesses the level of malnutrition and the kind of cancer, and draws a diet plan, which is a combination of supplementation as well as food. Cuddles also provides mid-day meals.

Then there is the ration basket, where Cuddles chooses families, mostly from low-income groups, with a high probability of abandoning treatment. They give them a monthly ration, comprising all major food categories, for a year. “This is a powerful programme which is very close to our heart. We’ve not been able to give it scale because it’s expensive.”

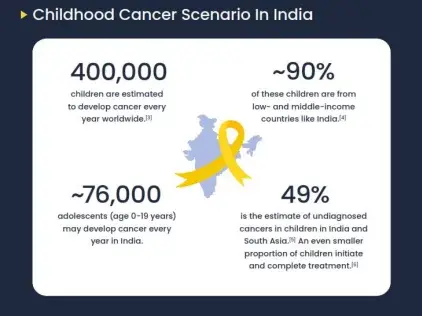

With something as simple as providing nutrition, Cuddles has seen that treatment abandonment rates drop from 20% to less than 3%. “With just nutrition, you can save 4,000 kids every year. It looks like a small number, but if you were to think of it, it’s a classroom full of kids disappearing every single day.”

Most government-funded hospitals, Ms. Dutta says, do not have the money to give patients nutritious food. At one such well-known hospital, breakfast is two slices of bread and half a cup of tea. “So we go there and say we will give you butter, egg, lassi and a banana.”

There’s one other reason nutrition is important. Most children are admitted with leukaemia. The treatment is chemotherapy, which is administered according to body weight. If the child’s body weight is not optimal, the hospital cannot give her the required dosage.

Nutrition counseling

Cuddles also does nutrition counseling and follows up with parents every month, besides in-hospital meal supplementation. “Weight loss in the child is a sure indication that they’re losing the child. So while weight gain is our dream, a stable weight is a realistic target.” But this is a big challenge with cancer treatment: children undergoing chemotherapy are often not able to eat. “Your gut, digestion, everything is compromised.”

Often, Ms. Dutta would walk into hospitals and see parents, with their limited financial means, buy fruit from roadside stalls, scoop the soft flesh out with their hands and give it to the children. But these children have low immunity, and get diarrhea. “The child would survive cancer but not diarrhea. We do a lot of parental education and guidance around how to take care of their children in limited means. Most parents don’t know they can give ragi, jowar, or bajra, for instance. We also tell them to feed the children dalia, sabudana and peanuts. We give them recipes.”

Given that Cuddles works in government and charitable hospitals, where most patients are from less privileged backgrounds, nutritionists receive extensive training in empathy. “It’s very easy to speak to the children from a position of power. But you’re not going to get through to them.”

The other big part of their work is with doctors, who are what Ms. Dutta calls the ‘entry point’. “Once we tie up with the hospital, any child who walks in through that door into the pediatric oncology ward will be seen by our nutritionist. We are very careful to work with hospitals that have motivated doctors. Because they are the ones driving everything.” A lot of doctors at government hospitals have left high-paying jobs abroad and are working in constrained environments here. “Anything that helps them to better the treatment outcome, they’re gung-ho about,” she says. One of the leading pediatric oncologists at Tata Memorial, Dr. Brijesh Arora, a crusader for nutrition, is the Foundation’s guide and mentor.

Greatest challenge

Ms. Dutta’s greatest challenge so far has been creating awareness about Cuddles’ work among companies: Malnutrition is often not a focus under corporate social responsibility programmes. Another issue is infrastructure, which is basic: a work station for the nutritionist, and a relatively quiet place to talk. There is a high burnout rate in the nutritionists, who tend to be young — 26-27 years old — and “not yet hardened.” “In our meetings, nutritionists break down very often. It’s not easy working in hospitals. Infrastructure is not there, and we’re generally in crowded places that are hot and full of sick, crying kids.”

Cuddles is, Ms. Dutta says, “the only one of its kind in the world.” The biggest validation of the niche they are in came from last year’s President’s Award. The Foundation has even designed curriculum for pediatric oncology nutrition, a super specialisation that SNDT has recently started offering. The next step is to cover 80 per cent of all the children who are under treatment in the country by 2018, and then move to haematological diseases and AIDS. Eventually, says Ms. Dutta, “we want to give food to every single child who’s in hospital.”

Sense of fulfillment

The work she does with Cuddles, she says, is the most fulfilling part of her life. Along with the challenges, she gets to hear the success stories. Like Nandu, whose parents abandoned him in the corridors of a government hospital when he was barely 11 years old. He used to go to a factory close by, earn daily wages for his meals, come back and seek treatment. “We adopted Nandu’s nutrition and he didn’t have to go to the factory. His treatment outcome improved, he’s doing well, and now he’s going to school.”

Support from her husband at home (the baby who is just as old as Cuddles is now six, and they also have 20-month-old twins) and from her business school (professors who have helped her with understanding how to raise funds or write a research paper), the pride in building something from scratch, and meeting the kind of selfless people she does in the course of her work keep her going. Still, when she’s unsure of what she is doing, she just has to walk into a hospital “and see these little kids, and it’s all very clear.”

Link to the original post here

Published on February 02, 2017

The Hindu